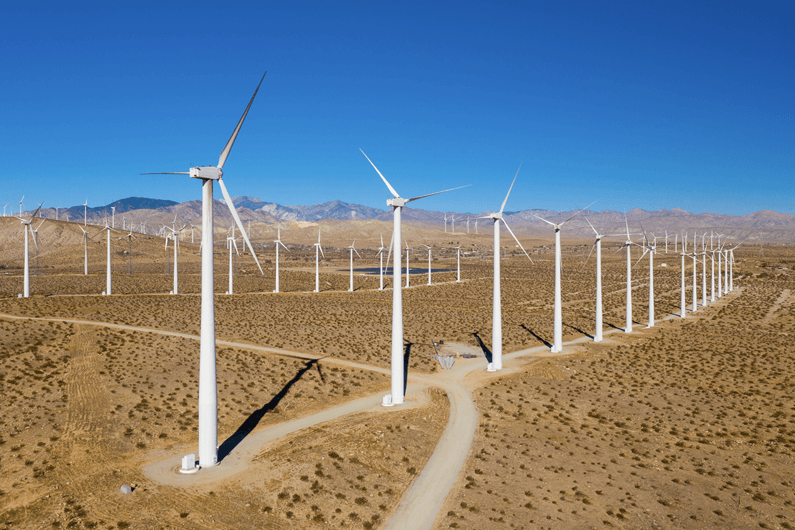

The Demand for Wind Energy Increases as Prices Lower

The decreasing price of wind energy prompts competitiveness among wind energy providers.

In a world struggling to cope with a changing climate, the wind offers today's commercial and industrial corporations an affordable, renewable energy source. Many large companies are now entering into long-term power purchase agreements with private wind power project developers at competitive power prices. As companies consider their energy needs, wind power is increasingly an option worth considering.

Compared to fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas, renewable energy—wind, hydro, solar, biomass and geothermal—are also carbon free or carbon-neutral power generation sources that are supportive of long-term, global carbon reduction goals. These attributes support the continued, long-term development of incremental wind power generation in the U.S., which in 2021 constituted about half of renewable-energy use and 9.2% of overall energy generation, according to the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy at the U.S. Department of Energy.

"Climate concerns aside, renewable energy provides tangible benefits to a business's bottom line through competitive power prices, and there is a strong economic case to be made for larger companies to switch to wind power, in whole or in part," says Richard Butler, Group Head of Energy, Power and Renewables at Fifth Third Bank. In fact, some of the world's most prominent corporations have already made the leap, including Amazon, Google and others, not only in the tech sector, but increasingly in a wide range of other industries, such as retail, telecommunications, food & beverage, automotive and healthcare, as well.

Why are Large Corporations Making the Switch to Wind Energy?

Start with the price of energy. Wind power is now more competitive than ever, with costs dropping 70% between 2009 and 2021, according to the American Wind Energy Association, an industry trade group. Power prices for the procurement of wind energy are typically fixed under long-term power purchase agreements, avoiding the volatile short-term fluctuations associated with wholesale power market prices. By using wind energy to reduce the cost of powering their operations, companies are also able to lower costs to their own consumers, stimulating sales.

Both the federal and state governments also incentivize the development and procurement of wind energy through tax subsidies and financing techniques such as tax-exempt bonds, loan guarantees, and affordable loans.

The Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit, or PTC, at the federal level is among the most common and beneficial tax subsidies in the U.S. wind industry. The PTC gives owners and developers of wind energy facilities a 10-year period during which they can take an income-tax credit at the federal level on every kilowatt-hour of electricity generated for the power grid.

Focused more on a company's reputation than on its finances, Renewable Energy Credits (also known as Renewable Energy Certificates) are, in effect, a tracking mechanism establishing that wind's zero-carbon electricity has been purchased. Customers, employees and many activist stakeholders appreciate such big-business sustainability efforts. Institutional investors seem to, too, as many expect to increase the portion of their portfolios devoted to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) fund products, according to a recent survey by consultants PwC.

Wind energy offers other opportunities for companies to better the lives of their customers and communities. Wind projects give large corporations the ability to help many communities through increased tax revenue, jobs and income; one mega-retailer buys its wind energy from a dozen different projects.

Virtual Purchase Agreements

Many new corporate entrants in wind energy are procuring wind power through the mechanism of Virtual Power Purchase Agreements or VPPAs. These are long-term financial contracts to buy wind power from a specific wind project. VPPAs are financially settled at a liquid wholesale power market trading hub (which removes potential power price basis risk to the corporate buyer), but without the expectation that the corporate buyer will actually receive the physical power it is paying for under the terms of the contract. However, the corporate buyer will receive the Renewable Energy Credits that are associated with the underlying energy generation from the wind project.

Looked at narrowly, the VPPA acts as an energy-price hedge for both the corporate buyer and the wind project, centered around the potential financial benefits and renewable energy attributes shared between the parties. More broadly, the VPPA the corporate buyer entered into in order to become a guaranteed, long-term "virtual" customer of the wind project facilitated the development—and the outside financing—of the wind project in the first place. This boosts the corporate buyer's reputation with its stakeholders in terms of its commitment to sustainability and garners it those coveted Renewable Energy Credits.

Washington Works for Wind

In addition to more established tax credits and financing techniques, the federal government over the past year has renewed funds for the wind power industry, particularly offshore. The $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, signed into law in November 2021, allots up to $50 billion to bolster clean power, $65 billion to upgrade transmission infrastructure and another $17 billion to improve the nation's ports, a current clog in the wind power system.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which became law in August 2022, supports domestic energy production as well as the reduction of carbon emissions. Importantly, the IRA also appropriated $100 million to plan, model and analyze "the economic, reliability, resilience, security, public policy and environmental benefits of interregional electricity transmission and the transmission of electricity from offshore wind energy generation."

In addition, the IRA buttressed support for offshore wind energy with the Energy Investment Tax Credit, or ITC, a one-time credit based on the dollar amount invested. Owners and developers of offshore wind farms whose construction begins prior to 2026 can earn a 30% tax credit. The act also reopened areas off the coasts of the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, both in the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, for offshore wind leasing.

Challenges

To the potential downside, however, the Inflation Reduction Act set new limits on the Department of the Interior's authority to issue offshore and onshore renewable energy leases. For the next decade, the Act ties the department’s ability to issue leases for offshore wind development to oil and gas leasing on the outer continental shelf in the previous year, according to the Congressional Research Service. Onshore wind power leases on federal government lands are also linked to activity in the oil-and-gas sector.

Environmental issues abound, however. Wind turbines, for instance, are coming under criticism for how difficult they are to dispose of at the end of their 20-to-25 year life cycle. Right now, they can be sent to a landfill, incinerated or recycled, but only about a third of the plastic material used in the blades can resurface in some other product. With thousands of new wind turbines being built and thousands of existing wind turbines approaching the end of their useful lives now, it is a problem in need of a long-term solution if the wind industry is to avoid reputational damage.

One such solution may be re-powering (replacing an older turbine with a new one), if only because it allows wind farms to take advantage of the latest technology to reduce the total number of turbines on a property. At one of the world's oldest wind farms, Altamont Pass in California, one re-powered turbine can do the work of 24 established turbines—making it easier for wind power to co-exist with birds and their migratory patterns.

Finally, it's folly to underestimate the potential for community opposition to wind farms—both onshore and offshore - typically when they are sited in the specific community’s proverbial "backyard." Wind turbines, which have been growing substantially in size (but also pressuring the profits of their manufacturers), have come under fire from some communities for being noisy and unsightly, as well as potentially harming birds.

A new approach to wind power may have promise by delivering local solutions to local problems, according to a recent article by 10 professors in the sustainability magazine Joule. The key, the authors say, is to encourage community involvement in the project design process from the get-go, and then incorporate the feedback into the actual engineering, rather than the opposite way around.